![]()

Intelligence Research Observatory

La Petite Guerre, Native American Warfare Culture, How it Influenced Small Wars, Modern Guerrilla Warfare and Special Operations

This Paper is dedicated to the Memory of Dave Dilegge, Founder of Small Wars Journal. Thank you Dave for helping so many of us get a start as Military Authors, Analysts, Leaders and Critical Thinkers. The Small Wars and Intelligence Community will never be the same without you.

Methodology-OSINT research

Caveat-This Article is an open sourced research paper, which sheds light on the valuable contribution of Native American Warrior culture to modern day light infantry tactics, Guerrilla Warfare, and special operations. Information is historical and there are instances where data is challenging to corroborate. The Native American perspective may be different from what their adversaries have recorded. American Native history is based in the culture of story telling and the author believes that oral histories may have been lost presenting gaps in information. The author of this paper has a deep respect for all indigenous peoples and their great culture. The Native American Warrior was a highly skilled soldier and expert small wars practitioner that deserves appropriate credit and respect for the way Small Wars are fought today.

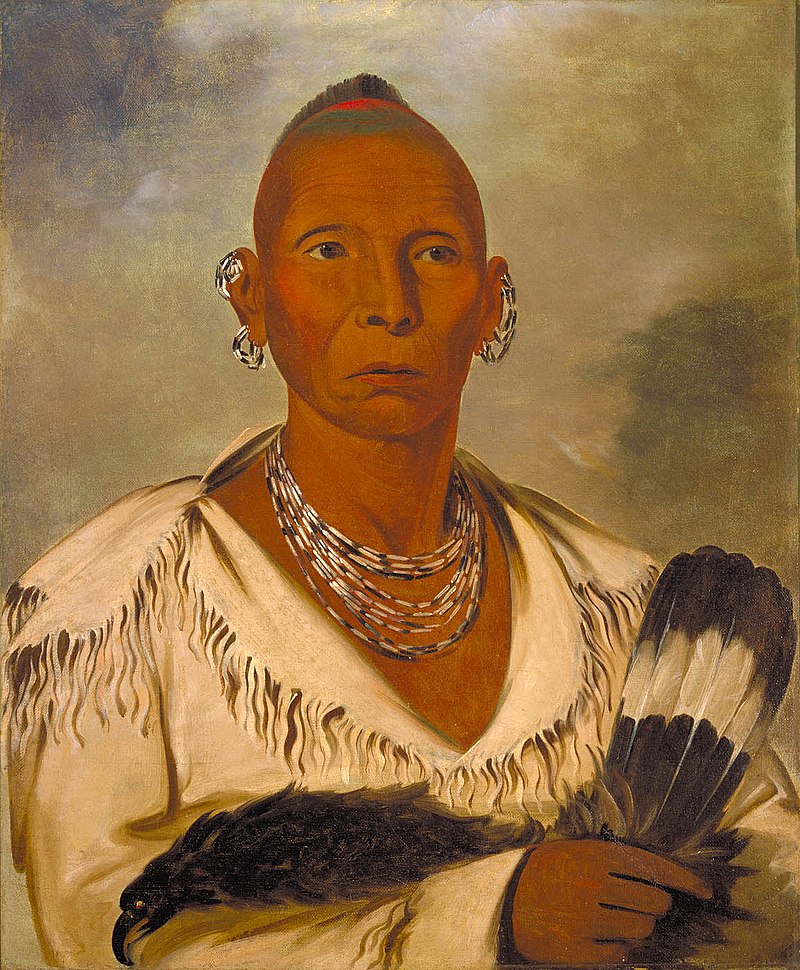

‘White Cloud’, Head Chief of the Iowas, 1844-45-Portrait by George Catlin

Background & Analysis

Native American Warriors were highly skilled soldiers, masters of woodland warfare and experts at conducting “La Petite Guerre.” The Native American Small War was a fusion of martial pragmatism, devotion to indigenous culture, and the survival of the family unit and tribal community. Native American Warriors were initially seen as undisciplined and unprofessional by their European adversaries. This assessment of Native American Warrior culture and skill was far from accurate. Native American Warrior culture and strategy was professional, intelligent, resourceful and functional. Small battles were conducted in a manner that conserved human resources and avoided unnecessary loss of skilled warriors. War Parties had specific purpose, and were conducted to achieve important objectives. Long drawn out battles were seen as a waste of resources when the objective could be accomplished with a short decisive engagement. Adversaries were given lines of retreat to allow for a quick end to battle. Native American soldiers were expected to retreat from the battlefield if engaging a superior enemy, there was no dishonor in the common sense of survival and consolidation. Warrior Braves expertly recovered their dead brothers the same as professional military units do today. American Native Warriors embraced asymmetrical warfare and fought battles in the frontier woodlands using the terrain and natural features as cover. European Army officers preferring conventional war became frustrated with Native Americans, their swift light infantry and lightening fast guerrilla tactics. Native American War Parties would strike quickly and use terrain to their advantage. Warrior Braves avoid open fields and retreat in a manner that drew their enemies into dangerous spaces. Once the adversary was at a tactical disadvantage, ambush and counter attack were launched. The French military was the first to see the merits of Native American Guerrilla warfare, and improved odds by employing native warriors as scouts and officers. The British Army was slow to accept native warriors as highly skilled infantry, superb strategists and expert irregular soldiers. British forces eventually adapted irregular warfare methodologies and transferred Native American frontier skills to the troops. Native American War Chiefs and Officers clearly defined objectives for warrior braves and allowed them latitude to freelance the battle space. Independence and autonomy afforded immediate reaction, fluid manoeuvres and exceptional results. Attacking at dawn allowed Native American soldiers the ability to reconnoiter the enemy under cover of darkness and move silently to the objective. Morning combat was functional for tribal security; warrior braves could return to the village, protect the family unit, and if necessary fight off counter attacks. This preserved family resources, while keeping the tribal community viable. Native American irregular warfare tactics were not lost on American frontiersman and British officer Major Robert Rogers. Rogers saw the genius of Native American Guerrilla warfare and developed doctrine, which focused on smaller, light infantry operations, able to spy and collect intelligence that would be vital for future counterinsurgency missions. Rogers’ Ranger manual was revolutionary because he attempted to render the art of wilderness warfare as a skill that one could teach and something that was transmittable as military doctrine. While the rangers were not viewed as the ultimate fighting or counter-insurgency force at the time, the foundation laid by Rogers would prove to be vital in the American Revolution for the Americans and for hundreds of years to come in the United States military and special operations units around the world.

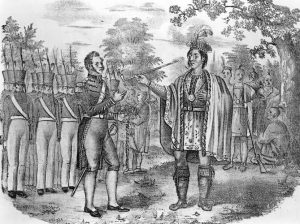

Conclave between Pontiac and Rogers’ Rangers-Library of Congress-Print of Pontiac (ca. 1720-1769) greeting Robert Rogers (1731-1795), ca. 1766.

Native American Guerrilla Warfare -Terminology & Terms of Reference

- La Petite Guerre -translated from French is “The Little War”

- The “Little War” -consists of light infantry that moves swiftly and employs hit-and-run tactics (Goetz, 2013)

- Small Wars Doctrine -is based in parts on Native American La Petite Guerre; these same tactics are used by modern-day U.S. Special Forces, specifically the Army Rangers (Goetz, 2013)

- Native American -refers to the indigenous people of North America, In the United States, the term “Native American” is in common usage to describe Aboriginal peoples (Indigenous Foundations-UBC, 2009)

- Native American Warrior -refers to a North American indigenous person that engages in warfare, raiding parties, hunting parties, inter tribal conflict & mourning parties

- A Brave –is a Warrior, especially among North American Indian Tribes (Dictionary.com, 2020)

- Mourning Parties -an activity of tribal ritual, it consisted of Warriors raiding another tribal territory, capturing another tribes member(s), who were then enslaved, assimilated, tortured or executed. The practice was to either replace a member that died or was killed; alternatively it was a way of mourning a lost tribal member

- Native American War Party -refers to a group Native American Warriors that are engaged in the activity of warfare, examples include but are not limited to raids, hunting, ambushes, small wars or national wars

- First Nations Warrior -refers to a Warrior of the First Nation

- First Nation -a term used to describe Aboriginal peoples of Canada who are ethnically neither Métis nor Inuit, this term generally replaced the term “Indian” (Indigenous Foundations-UBC, 2009)

- First Nation -can refer to a band, a reserve-based community, or a larger tribal grouping and the status Indians who live in them (Indigenous Foundations-UBC, 2009)

- First Peoples -first inhabitants of North America

- North American Guerrilla Tactics (British, French, and American) -were first adopted during the French and Indian Wars by a colonial solider, Major Robert Rogers (Goetz, 2013)

- American & European Guerrilla Tactics -known as Ranging, Wilderness warfare, and Frontier fighting

- Rogers Rangers –an infantry unit lead by Major Robert Rogers, which engaged in irregular warfare known as the tactics of Ranging (Goetz, 2013)

The Death of General Wolfe- Benjamin West 1770-National Art Galley of Canada

Key Points

Native American Small Wars Culture

- When Native American warriors encountered overwhelming odds they were expected to run

- Faced with no win conditions, warrior commanders and his soldiers covered retreat (Eid, 1988)

- Warrior Braves were legendary for retrieving their dead (much as modern professional soldiers do today)

- It was never a disgrace for Native American Warriors to retreat from superior enemies forces

- European militaries considered flight of Native Warriors during battle to be unprofessional

- Native American warfare doctrine of tactical retreat was intelligent and economical

- Warfare conducted by Native American soldiers took into account military & human resources

- Native Small Wars were carried out so that Warriors were not unnecessarily killed in battle

- Lines of retreat and quarter were given to adversaries, so as to avoid long drawn out battles, which needlessly drained resources

- Irregular warfare preserved the loss of tribal people, this in turn improved long term survival of the community

- First Nation warrior culture placed strong emphasis on preserving the family unit

- Captured warriors were often integrated into tribes as replacements, skills were transferred & bloodlines improved (Eid, 1988)

Key Concepts of Native American Guerrilla Warfare

- La Petite Guerre-Native American war parties specifically avoided symmetrical and conventional European warfare

- Native American Warrior tactics were based on small raiding parties, hunting parties & ambuscades (Eid, 1988)

- Native American War Parties used surprise & lightening fast strikes

- Native Small Wars strategy was based on the cultural theory that small raiding parties & asymmetrical warfare allowed Warriors to survive conventional conflicts, allowing them fight battles on their terms later, at a place and time of choosing

- Native American warriors often retreated early as a strategy to draw adversaries into terrain that was tactically advantageous to the Native Warrior

- Braves and Warriors fought with independence and autonomy

- The independent thinking of warriors and their autonomy in the battle space allowed them to manoeuvre rapidly and adapt quickly

- Native Chiefs and Officers would impart the general goal of the war party to the warrior brave, this allowed them to freelance battle plans while working toward the objective

- Native American soldiers deployed psychological warfare to intimidate their adversaries

- The Native practice of scalping frightened conventional European soldiers and degraded their will to fight

- Scalping became an important aspect of Native American culture, and had a powerful psychological function

- Raids & Attacks were most often staged at dawn; this allowed warriors to silently approach and reconnoitre targets under cover of darkness

- Dawn attacks facilitated early morning combat; braves could then return to their villages and protect the tribe from counter attacks

- Native American War Chiefs took strategic advantage of the terrain

- Warriors and Braves used woodlands to engage adversaries, they would take cover behind trees and rocks, this was troubling for European officers wanting to fight conventional rank and file battles

- War Chiefs and Officers observed European military tactics and formations; they trained their braves to fight with their own brand of flexible & maneuverable formations

- The Native warrior half moon formation evolved from hunting methods, which entailed driving game to skilled hunters

- The half moon on the battlefield proved successful because it was logical, pragmatic and a fluid battle formation (Andress, 2019)

Adapting Native American Irregular Warfare Strategy

- Native American Irregular warfare tactics were so effective, European militaries had to adapt (Goetz, 2013)

- British and French militaries came to the realization that embedding Indian scouts and allied Native War Parties into their own apparatus increased their odds of winning in the wilderness battle space

- The European Armies would have to learn and use asymmetrical tactics and strategies to level the battlefield

- The challenges of adapting to irregular woodland warfare was in the mind set of the European commanders

- Native American Guerrilla warfare was considered un-gentlemanly and crude

- Frontier Companies and Irregular soldiers were seen as undisciplined and poorly organized

- This type of thinking proved inaccurate when considering the effectiveness of Ranger units and their asymmetric techniques

- Eventually European militaries and officers would embrace irregular frontier warfare practices from Native American Warriors (Goetz, 2013)

- Modern Special Forces and Ranger Companies employ Native American Techniques & doctrine learned from Native American Warfare

Comparing Native American La Petite Guerre to USMC Small Wars Manual

- The United States Marine Corps Small Wars Manual states “operations orders should usually be phrased in general terms and the details of execution delegated to subordinate commanders.”Thus, junior officers are given a great deal of latitude to prosecute the war as they see fit provided their actions support the overall strategy defined by senior leadership, and the enemy may be pressed to the fullest extent thanks to a flexible organization (Potter, 2015)

- Braves and Warriors fought with independence and autonomy in the battle space, this allowed them to manoeuvre rapidly and adapt quickly. Native Chiefs and Officers would impart the general goal of the war party to the warrior brave, this allowed them to freelance battle plans while working toward the objective (Andress, 2019)

The American & European Brand of Irregular Warfare

- French militaries showed early aptitude for Guerrilla style warfare, this is because the French Army partnered with First Nations Warriors sooner and in greater numbers

- Embedding Native American warriors and braves within the French ranks, helped the French adapt to frontier warfare and utilize indigenous skill sets

- The French employed braves as scouts and officers, native warfare culture and leadership became fixed within French battalions

- The British Army, was resistant to Native American warfare and culture

- Eventually the British saw the merit of Native American warfare and developed frontier fighting skills

- Native American Small Wars doctrine would become ingrained in European and American infantry elements and would be put into practice by Ranger battalions and Special Forces (Goetz, 2013)

Major Robert Rogers-Portrait-No Known Copyright

Rogers Rangers and the Techniques of Ranging

- Rogers’ ranging rules took the focus away from large military operations to smaller, light infantry operations that were able to spy and collect intelligence that would be vital for future counterinsurgency missions (Goetz, 2013)

- Rogers Ranger manual was revolutionary because he attempted to render the art of wilderness warfare as a skill that one could teach and something that was as transmittable as a military doctrine

- While the rangers were not viewed as the ultimate fighting or counter-insurgency force at the time, the foundation laid by Rogers would prove to be vital in the American Revolution for the Americans and for hundreds of years to come in the United States military and its special operations (Rogers, 1757) (Clark, ND)

Rogers Rangers Manual

- All Rangers are subject to the rules of war.

- In a small group, march in single file with enough space between so that one shot can’t pass through one man and kill a second.

- Marching over soft ground should be done abreast, making tracking difficult. At night, keep half your force awake while half sleeps.

- Before reaching your destination, send one or two men forward to scout the area and avoid traps.

- If prisoners are taken, keep them separate and question them individually.

- Marching in groups of three or four hundred should be done in three separate columns, within support distance, with a point and rear guard.

- When attacked, fall or squat down to receive fire and rise to deliver. Keep your flanks as strong as the enemy’s flanking force, and if retreat is necessary, maintain the retreat fire drill.

- When chasing an enemy, keep your flanks strong, and prevent them from gaining high ground where they could turn and fight.

- When retreating, the rank facing the enemy must fire and retreat through the second rank, thus causing the enemy to advance into constant fire.

- If the enemy is far superior, the whole squad must disperse and meet again at a designated location. This scatters the pursuit and allows for organized resistance.

- If attacked from the rear, the ranks reverse order, so the rear rank now becomes the front. If attacked from the flank, the opposite flank now serves as the rear rank.

- If a rally is used after a retreat, make it on the high ground to slow the enemy advance.

- When laying in ambuscade, wait for the enemy to get close enough that your fire will be doubly frightening, and after firing, the enemy can be rushed with hatchets.

- At a campsite, the sentries should be posted at a distance to protect the camp without revealing its location. Each sentry will consist of 6 men with two constantly awake at a time.

- The entire detachment should be awake before dawn each morning as this is the usual time of enemy attack.

- Upon discovering a superior enemy in the morning, you should wait until dark to attack, thus hiding your lack of numbers and using the night to aid your retreat.

- Before leaving a camp, send out small parties to see if you have been observed during the night.

- When stopping for water, place proper guards around the spot making sure the pathway you used is covered to avoid surprise from a following party.

- Avoid using regular river fords as these are often watched by the enemy.

- Avoid passing lakes too close to the edge, as the enemy could trap you against the water’s edge.

- If an enemy is following your rear, circle back and attack him along the same path.

- When returning from a scout, use a different path as the enemy may have seen you leave and will wait for your return to attack when you’re tired.

- When following an enemy force, try not to use their path, but rather plan to cut them off and ambush them at a narrow place or when they least expect it.

- When traveling by water, leave at night to avoid detection.

- In rowing in a chain of boats, the one in front should keep contact with the one directly astern of it. This way they can help each other and the boats will not become lost in the night.

- One man in each boat will be assigned to watch the shore for fires or movement.

- If you are preparing an ambuscade near a river or lake, leave a force on the opposite side of the water so the enemy’s flight will lead them into your detachment.

- When locating an enemy party of undetermined strength, send out a small scouting party to watch them. It may take all day to decide on your attack or withdrawal, so signs and countersigns should be established to determine your friends in the dark.

- If you are attacked in rough or flat ground, it is best to scatter as if in rout. At a pre-picked place you can turn, allowing the enemy to close. Fire closely, then counterattack with hatchets. Flankers could then attack the enemy and rout him in return. (Rogers, 1757) (Clark, ND)

Resources

A Kind of Running Fight’: Indian Battlefield Tactics in the Late Eighteenth Century Leroy V. Eid (1988) https://journals.psu.edu/wph/article/download/4105/3922

Definition of a Brave (Noun)-Dictionary.com (2020) https://www.dictionary.com/browse/brave

Absolutely Brutal (And Smart) Tactics In Native American Warfare, Justin Andress-Ranker.com (2019) https://www.ranker.com/list/native-american-tactics/justin-andress

Emory Endeavours in History 2013 A Country Dangerous for Discipline: The Clash and Combination of Regular and Irregular Warfare during the French and Indian War-Nicole Goetz-Emory Endeavours (2013) http://history.emory.edu/home/documents/endeavors/volume5/gunpowder-age-v-goetz.pdf

Rogers’ Rules of Ranging-Major Robert Rogers (1757)-Wesclark.com (No Date) http://wesclark.com/jw/rogers_r.html

Terminology-Indigenous Foundations-University of British Columbia (2009) https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/terminology/

Classics of Strategy and Diplomacy-The US Marine Corps’ Small Wars Manual (1940) -A. Bradley Potter (2015) https://www.classicsofstrategy.com/2015/09/small-wars-manual-marine-corps.html

Image-Conclave between Pontiac and Rogers’-Print of Pontiac (ca. 1720-1769) greeting Robert Rogers (1731-1795), ca. 1766. -Library of Congress (1912) https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2016646382/

Image-George Catlin – Múk-a-tah-mish-o-káh-kaik, Black Hawk, Prominent Sac Chief – 1985.66.2 – Smithsonian American Art Museum (1832) http://americanart.si.edu/collections/search/artwork/?id=3925

Image-depicting the famous confrontation between Tecumseh and William Henry Harrison at Vincennes, Indiana, in 1810-Source: Mid-Manhattan Picture Collection / American history (1818) https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/search/index?keywords=808986

Image-George Catlin – White Cloud Pixabay (2020) https://pixabay.com/illustrations/painting-artwork-art-george-catlin-1023398/

Image-Major Robert Rogers — Drake, Francis S. (Francis Samuel), 1828-1885 Dowd, Francis Joseph, 1876 (2020) Publisher: New York London : Harper & Brothers

Image-Benjamin West — “The Death of General Wolfe” 1779- The National Art Gallery of Canada (2020) https://www.gallery.ca/collection/search-the-collection?f%5B0%5D=field_reference_artist%253Atitle%3ABenjamin%20West&page=1