![]()

De Faakto Intelligence Observations

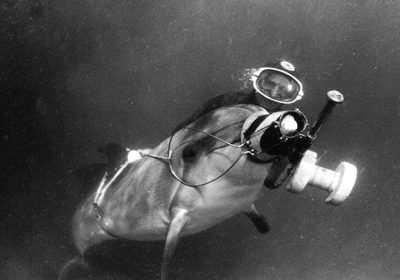

Belt & Road, Evolution of the Dragon, Hybrid Grey Zone Ops & Chinas Corporate Security Abroad

De Faakto Intelligence Analysis -S.A. Cavanagh

Methodology-OSINT research

Photo Courtesy of Belt and Road News (2020)

Background

Chinas Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) can only be described as the most remarkable & ambitious commerce undertaking in modern history. It is an immense Dragon in both size and scale. BRI encompasses 65 countries, 900 billion dollars invested, 870,000 Chinese nationals abroad working for 16,000 Chinese corporations; all this is taking place in some of the riskiest nations in the world. There have been Chinese casualties associated with the BRI, and it has not gone unnoticed in Beijing. Risk to Chinese citizens abroad includes; long-standing security problems, violent conflict, political instability, transnational terrorism, asset protection, riots, theft, petty crime, maritime security, anti-piracy, kidnap-ransom, civil war and natural disasters.

Analysis

Principal to the unstable conditions Chinese nationals must work in, there are secondary problems associated with securing Belt & Road investments. Chinese business practices have the potential to exacerbate regional problems, with low social/environmental standards, corruption and lack of transparency; this has created anti-China sentiment & pushback in many host nations. China Can Not Depend on Economic Development to Promote Security, and this is why Beijing needs private military and security contractors supporting the BRI. Beijing will not rely on local forces to provide security as police and military are sometimes underpaid, poorly trained and often corrupt. Chinese personnel report being subject to “legitimate harm at the hands of the military and police” while working in Iraq and the Democratic Republic of Congo. China states “it wishes to avoid interfering with any foreign country in a military capacity,” this policy will only expose China to risk. China hesitates to use private security contractors from other countries to protect Chinese nationals abroad because the cost associated with first world tier one-high risk security contractors can be prohibitive. China must find domestic solutions; evidence of this is Chinese security contractors countering piracy in the maritime shipping industry. China allows “Sea Dragons,” maritime security contractors, to deploy internationally, carry weapons and use force if necessary, while on state owned Chinese ships transiting pirate infested waters. Most Chinese corporate maritime security personnel are drawn from the ranks of the Peoples Liberation Navy, notably from the officer’s corps, and naval Special Forces, amphibious reconnaissance forces, and Marine Corps. Former PLA navy personnel engaged as private security contractors will represent the interests of Beijing consistently, because 80% of Chinese maritime security contractors are members of the communist party of China.

Photo Courtesy of Ministry of National Defense The Peoples Republic of China (2020)

Hybrid Warfare or Legitimate Security Solutions-Beijing Does not Differentiate Between State and Private Security Assets Abroad

Three Case Studies-of China blurring the line, by-with-and-through, state military, maritime militia, private military & private security contractors operating around the globe

1. In 2016 when Chinese citizens were stranded between warring militias in South Sudan, DeWe Security contractors secured and evacuated Chinese workers. Working unarmed DeWe personnel, retained armed South Sudanese soldiers to support a rescue mission; concurrently Beijing’s allies in the Ugandan Peoples Defense Force secured the airport for the extraction of Chinese nationals. This all took place while Chinese troops on UN mission remained garrisoned nearby; this was done to avoid the potential of a national incident with Chinese troops working abroad.

2. It is no secret that China operates a maritime militia, a citizen naval reserve made up of civilian sailors, retired navy personnel and fisherman. Chinese maritime militia use civilian fishing boats to conduct important naval special activities; espionage, intelligence, surveillance, reconnaissance, sabotage, contested water skirmishes, obstruction, reef/island development, mine laying, concealment missions, spying and ambush. The maritime militia is exceptional in two areas of operations; missions that require small commercial vessels which can linger unnoticed for long periods of time, and obstruction missions where contested waters are saturated with Chinese flagged vessels. This private “contractor like-hybrid fusion civilian Navy” made up of worn out, innocent looking fishing boats, is suitable for asymmetrical, grey zone operations, and can engage aggressively in activities that would normally lead to conventional naval warfare. This same strategy will be applied to Chinese state security companies working abroad. Security Contractors will act on behalf of the state managing grey zone operations that Chinese military units can not be seen engaging in. Security contractors provide plausible deniability for the state.

3. The Chinese PLAN (Peoples Liberation Army Navy) has acquired a naval base in Djibouti. Djibouti is a principle BRI benefactor. The PLAN is able to carry out training on foreign soil and African waters. Chinese private security and military companies established in BRI nations can develop secure company paramilitary bases, which can be occupied later when needed by the PLA/PLAN. Chinas reclamation of reefs and construction of naval bases which occupy other nation’s sovereign territory in the South China Sea is another instance of China claiming innocuous civil infrastructure, for weather stations and vacation islands. China later occupies the islands with hardened military infrastructure, garrison troops and deploys advanced air defense and anti-ship missiles. This is all done despite Chinese President Xi Jinping’s nominal 2015 pledge not to militarize the islands and the Foreign Ministry’s claims that these “necessary defense facilities” are provided primarily for maritime safety and natural disaster support.

Photo Courtesy of LinkedIn (2018)

Analysis-Sino Partnership, Erik Prince and Frontier Services Group

Open source intelligence indicates that Beijing is serious about building a strong private military and corporate security footprint abroad. CITIC Group, a state run investment fund owned and controlled by the Peoples Republic of China is the largest shareholder in Erik Princes’ Corporation, Frontier Services Group. Erik Prince is considered by some as the father of modern private military companies. Prince a retired US Navy SEAL is the founder of Blackwater USA. Prince realized before most of his peers the opportunities in the lucrative Chinese market for security forces. Frontier Services Group (FSG) is a diverse company operating logistical projects with shipping routes in Africa, and conducting high-risk evacuations from conflict zones. FSG, however does not provide services involving armed personnel or training armed personnel. As part of Prince’s Africa-focused investment strategy, FSG purchased stakes in two Kenyan aviation companies, Kijipwa Aviation and Phoenix Aviation, providing logistics services for the country’s oil and gas industry. Prince also has a 25% stake in Austrian aviation company Airborne Technologies. In 2014, Prince commissioned the company to modify Thrush 510G crop-dusters with surveillance equipment, machine guns, armour, and other weapons; this included custom pylons that could mount either NATO or Russian ballistics. One of the modified crop-dusters was delivered to Salva Kiir, Mayardit’s forces in South Sudan shortly before a contract with Frontier Services Group was cancelled. Frontier Services Group owns two of the modified Thrush 510Gs, but since executives learned the craft had been weaponized by Prince, the company has declined to sell or use the aircraft to avoid violating U.S. export controls. In December 2016, FSG announced its plans to set up a “forward operating base” in Yunnan to provide logistics and unarmed security training services to facilitate One Belt, One Road-related projects in Southeast Asia. As part of FSG strategy to set new industry standards, Prince acquired a 25 percent ownership stake in the International Security and Defense College in Beijing, which trains Chinese security contractors and managers for international deployment. Perhaps one of the best indicators of Beijing’s intentions to use private military/security companies to achieve the Belt and Road lies in the fact that it has partnered with Erik Prince, the most forward thinking and accomplished mercenary chief, to advise and assist Chinas fledgling corporate military security apparatus. China has demonstrated the ability to shape shift Chinese assets, corporate or state owned. Beijing will continue to leverage Chinese private military/security companies abroad, to achieve Belt and Road, and any other Chinese agenda, including Chinas strong appetite for regional power and influence.

Photo Courtesy of Belt and Road News (2020)

Intelligence Research Notes & Observations

Belt & Road Initiative-Security for Chinese Projects & People

- As the Belt and Road Initiative expands into countries with security problems, the risks associated strengthen the case for the Chinese government to secure its companies and citizens working abroad

- The Belt and Road Initiative involves 65 countries

- $900 Billion invested by China in the Belt and Road

- 847,000 Chinese Nationals at risk for violence, kidnap & ransom, piracy, natural disasters

- 16,000 Chinese Companies abroad in areas of risk (International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2019)

Chinese Nationals Abroad, It’s Not Just About Belt & Road

- It should be noted that 100 million Chinese nationals travel abroad annually

- With so many Chinese nationals working, and traveling abroad, it makes sense for Beijing to have Sino PMC/PSC assets which can be called upon to provide assistance with hostage negotiations, rescue, medical evacuations and consular assistance

- The greater the reach of Chinese security companies abroad, the more efficient the solution for Beijing

- Chinese private security companies (PSCs) are latecomers to the African security sector and their services are unrelated to the provision of military services or the delivery of military equipment

- At present, China’s PSCs are still evolving from local security enterprises operating in low risk environments in Mainland China into international companies able to maneuver abroad in high-risk areas

- Africa is the litmus test for Chinese PSCs, with tasks including asset protection from riots, theft, terrorism and maritime anti-piracy missions (Arduino, 2020)

Why Beijing Needs Private Military & Security Contractors Abroad

- Although Beijing would like to rely upon local forces to provide security, host government authorities may be unable or unwilling to provide Chinese workers and businesses with adequate protection

- The very weakness of many states in which China invests, means that military and police bodies are often underpaid, overstretched, poorly trained, and driven by the same tensions affecting the state

- For instance, Chinese personnel working in the Democratic Republic of Congo report of routinely being subject to “legitimate harm” at the hands of soldiers and police officers

- In Iraq, one Chinese business called upon the local police in response to looting only to see the responding officers join in the fray

- The dangers Chinese citizens and operations confront overseas and the varying responses of local forces have caught the attention of Chinese officials

- In 2012, the People’s Daily, the official newspaper of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, printed the following: “China should deeply study the diplomatic protection issue… China should also discuss how China strengthens its diplomatic influence… so that China can safeguard its national interests and protect its citizens to the maximum extent” (Eurasia Review, 2020)

China Can Not Depend on Economic Development to Promote Security

- Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) has expanded into countries with new or long-standing security problems, including violent conflict, political instability, and transnational terrorism

- The risks associated with working inside unstable countries and regions has already resulted in Chinese casualties

- Not only are Chinese companies and nationals a target for terrorist or separatist-fuelled violence, but BRI also has the potential to exacerbate local, regional, or national security issues in the countries through which it passes

- Expensive projects can lead to substantial debt in host countries and create opportunities for corruption where transparency is lacking at the national level

- Low social and environmental standards can also fuel tensions within local communities, causing anti-Chinese pushback against BRI, as seen in Pakistan, Vietnam, and Sri Lanka (International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2019)

THE AFRICAN CONTINENT’S THREAT SPECTRUM encompasses all the risks, from criminal to political violence that public and private Chinese companies are going to experience throughout the Belt & Road Initiative

- From Libya to South Sudan, China has witnessed how severely limiting the sole reliance on economic development to promote security and sustainable development can be

- As such, security is an increasingly important priority, especially for Chinese companies operating in politically volatile areas (Arduino, 2020)

What is a PMC versus a PSC?

The role of Private Security Contractors (PSCs) is quite different from the role played by Private Military Contractors (PMCs)

- PSCs provide passive security services, mainly guarding personnel and infrastructure against theft or acts of violence (Arduino, 2020)

- PMCs provide paramilitary services ranging from logistics support, intelligence gathering, Special Forces training, emergency evacuations, anti-piracy protections, fixed emplacements security, and tactical support involving the pre-emptive use of force (Arduino, 2020)

PMC/PSC Disguising between the Peoples Liberation Army/Navy

- The case for the Chinese government to secure its companies and citizens working abroad is thus a compelling one from Beijing’s perspective

- Beijing has had to calculate whether to employ national military resources, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), or use other means to do so

- Although China has experience in utilizing military and paramilitary forces for national security in its domestic context—against separatist movements in western China, for example—it has chosen not to use the PLA to secure BRI projects

- Doing so would be inconsistent with its long-standing policy of non-interference in other countries’ sovereignty, potentially damage diplomatic relations with neighboring countries, test a military that has lacked combat experience since the late 1970s, and require greater investments in military logistics and infrastructure

- Instead, Beijing has turned to Chinese private security companies (International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2019)

State Owned Entity & Private Security Blurring the Line

- One of several problems related to Private Security Companies (PSCs) begins with the lack of an unambiguous and mutually agreed definition of what a private security firm really is

- When PSCs pre-emptively use an armed response or act as force multipliers providing security training

- Unclear boundaries associate mercenaries with private security companies, private military corporations, or global corporations that provide hybrid services

- Further important questions that must be answered include whether the Chinese PSCs will take orders from the government and whether Beijing is going to frame a clear code of conduct and related rules of engagement

- Assume, for the sake of argument that some sort of crisis occurs in a far-off country that involves dozens of Chinese nationals. In this hypothetical case, assume that a local terrorist organization has kidnapped Chinese workers and is threatening to kill them unless Beijing pays a ransom or provides political support for the terrorists’ cause. If a local PSC is operating in the area, is it going to negotiate on behalf of the Chinese government or undertake kinetic action on its own authority? While a debate is open in Beijing there is still a long way to go before the necessary capabilities are developed, including a code of conduct and most importantly the chain of command and responsibilities (The Diplomat, 2018)

- A similar conclusion was made by the Mercator Institute for China Studies, which argued that “Chinese PSCs are entirely under the control of the state, through the Ministry of Public Security. It is the opinion of some analysts that, based on available references, statements of notable Chinese figures, and PRC political traditions, it is unlikely that Chinese PSCs operate independently of the state (Sukhankin, 2020)

DeWe Security Services Group, Blurring the Line, A Case Study of Private Security Acting as a State Entity

- In South Sudan, DeWe handles security for the China National Petroleum Corporation, which operates that country’s oil-producing and export infrastructure. DeWe contractors have, however, been called into action before. In July 2016, Chinese peacekeepers stationed in Juba, South Sudan, remained in their bases during fierce fighting that left 330 Chinese workers stranded between warring militias in ten different locations around the city. Such inaction came despite the fact that protecting oil workers and assets is included in the peacekeepers’ UN mandate. The job of evacuating the workers was left to DeWe Security Services Group. DeWe’s personnel were unarmed, and its facilities could not be used as assembly points because they lacked ballistic protection. DeWe’s senior management then enlisted armed South Sudanese as backup and ordered the stranded Chinese nationals to hunker down where they were. Only when Ugandan forces secured the airport did the extraction proceed. Beijing’s close ties to the Uganda People’s Defense Force played a major role in the success of this operation (Nantulya, 2020)

Photo Courtesy of People’s Daily Online (2013)

Grey Zone Warfare

- PMCs were effective and continue to be valuable for the United States in Afghanistan, Iraq and many other locations outside the continental US

- PMCs are extremely useful for Russian grey zone operations as exhibited recently in Crimea, Syria, Libya throughout Africa, Sudan, and Central African Republic

Opening Chinese Military Bases Abroad Using PMC/PSC to Establish Overt Paramilitary Infrastructure

One hypothesis is that China will raise a private army using the pretext of protecting corporate entities, while concurrently garrisoning paramilitary forces in foreign nations; this would be a suitable back channel for China’s policy of not interfering militarily with sovereign nations, all the while constructing clandestine PLA/PLAN bases under the guise of PSCs or even PMCs (De Faakto, 2020)

- A recent example of China building military bases in foreign territories is the reclamation and development of reefs in South China Sea, initially China claimed the islands would be used for weather stations and communications infrastructure (Cavanagh, 2018)

- The islands became hardened military bases, with naval bases, harbours, garrisoned soldiers and military radar stations (Cavanagh, 2018)

- While Chinese PSCs’ footprint is limited to a handful of countries, Africa is witnessing the return of well structured groups of international Private Military Companies (PMCs) who support local governments and international interests external to the African continent

- The most recent example of this phenomenon is the growth of Russian Para-military contractors-China likely wants to emulate this practice

- While many Chinese PSCs are still flying under the radar, attention to the Chinese military and its peace building presence in Africa is on the rise

- China’s security relations with Africa have advanced considerably over the last two decades

- In 2015 a revised counter-terrorism law amplified the scope of Chinese military overseas deployments This law was enacted the same year that China’s Africa Policy called for broader military-to-military engagement in terms of capacity building and security technology transfer with African states

- Therefore, it is not by chance that just after the opening of the naval base in Djibouti, China started to train its military forces on African soil

- The training ranged from live fire exercises to helicopter evacuation drills from a PLAN frigate off of Djibouti’s coast

- During 2018 alone, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) conducted training in Cameroon, Gabon, Ghana, and Nigeria

- At the same time, army medical units operated in Ethiopia, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Zambia

- Beijing’s participation in UN Peacekeeping Operations in Mali, Sudan, and the PLAN’s participation in international counter-piracy missions in the Horn of Africa and the Gulf of Guinea showcase the country’s efforts to fight terrorism and piracy as part of the China-Africa Action Plan (Arduino, 2020)

Photo Courtesy of African Quarters (2019)

Plausible Deniability-Learning from Russia’s Wagner Group

- China without question has been observing the grey-zone activities of Russia’s PMC Wagner Group

- Wagner Group, is a private military company (PMC) used to outsource military tasks to achieve Russian foreign policy. Wagner was founded by Dmitri Utkin a former Russian Lieutenant Colonel, Spetsnaz Special Forces operator. Wagner is fronted by Russian businessman Yevgeny Prigozhin (Putin’s Chef). It is thought that Wagner is controlled by FSB and GRU officers. Wagner has conducted military operations in the Ukraine, Syria, Libya, Central African Republic and Sudan. Tactical combat capabilities of Wagner include: infantry, heavy artillery, air defense, armored tanks, training advisory and intelligence. PMC Wagner conducts proxy and hybrid warfare and is used to secure high value infrastructure central to Russian foreign policy (Cavanagh, 2018)

- Wagner has the advantage of controlling the flow of operational information. This enables activities to go unnoticed, avoiding negative public opinion. The death of contract soldiers draw less attention then Russian state troops killed abroad. PMC contractors like Wagner, are elemental for conducting Russian military strategic doctrine. Wagner is central to Russia’s efforts to project power and influence in former soviet era regions of alliance and secure new opportunities that accomplish Russia’s foreign agenda (Cavanagh, 2018)

- China now exposed to significant risk in the BRI, will likely emulate and adopt concepts of the PMC Wagner model as either policy or as a necessary unconventional option should BRI investments or Chinese geopolitical agenda be at risk

Photo Courtesy Africa Intelligence (2020)

Frontier Services Group & Erik Prince, Mentor & Partner, Chinese Private Military Contractors

- As the Chinese military has not been involved in a war since 1970, lacks logistical capacity, and is state operated, there is no expertise or understanding of how to develop a private military corporation

- Chinas approach to global military competition has been to purloin and reverse engineer other nations’ military technology, equipment and tactics, often adding value and improving the model for its own apparatus

- This is where Blackwater founder and retired US Navy Seal, Erik Prince is able to advance the Chinese PMC model

- Opposing nations perceive Chinese counterparts as second tier operators and possible clients for advanced services ranging from K&R special insurances to advanced risk management solutions. In Washington, from the private sector point of view, there is a massive confidence gap to overcome. The notable exception in the US is related to Erik Prince. Defined as “America’s foremost mercenary executive” Prince, Blackwater PMC’s founder, realized before most of his peers the opportunities in the lucrative Chinese market for force

- Erik Prince was one of the lead founders of the PMC “Blackwater USA” in 1997. The company has gone through multiple name changes over time, to include “Xe” in 2009, and then “Academi” in 2010. Prince left his formal positions with the company in 2009. Academi continues operations as a component of the Constellis Holdings Group, an umbrella company for multiple PMCs (Jamestown, 2020)

Frontier Services Group Executive Leadership

- Zhenming Chang Non-Executive Chairman of the Board

- Dongyi Hua Chief Executive Officer Executive Director

- Chun Shun Ko Executive Deputy Chairman of the Board

- Ning Luo Executive Deputy Chairman of the Board

- Erik D. Prince Executive Deputy Chairman of the Board

Frontier Services Group (FSG)

- Founded in Hong Kong by Prince in partnership with the Chinese state financial conglomerate CITIC group and with an office in Beijing, was branded in 2014 as an advanced service and logistics company supporting the Chinese extractives sector in areas such as South Sudan During 2018, FSG’s business scope was upgraded to include the intent to build training centers for the Chinese private security sector in China. While training camp projects seem to have been put on hold, FSG is set to capitalize on China’s economic expansion in Africa and on their related need for security. According to Bloomberg, the China-FSG cooperation model in Africa ranges from security protection in Somalia, to running air ambulances out of Kenya, and support for Chinese mining operations in the DRC and Guinea (Arduino, 2020)

Photo Courtesy of Arab Unreported (2019)

Frontier Services Group-Operations

- The company operates logistical projects for shipping routes in Africa

- FSG conducts high-risk evacuations from conflict zones

- FSG does not provide services involving armed personnel or training armed personnel

- Frontier Services Group has ties to the CITIC Group, a state-run investment fund owned and controlled by the People’s Republic of China

- CITIC is FSG’s largest shareholder

- As part of Prince’s Africa-focused investment strategy, Frontier Services Group purchased stakes in two Kenyan aviation companies, Kijipwa Aviation and Phoenix Aviation, to provide logistics services for the country’s oil and gas industry

- Prince also purchased a 25% stake in Austrian aviation company Airborne Technologies

- In 2014, Prince commissioned the company to modify Thrush 510G crop-dusters with surveillance equipment, machine guns, armor, and other weapons, including custom pylons that could mount either NATO or Russian ballistics

- One of the modified crop-dusters was delivered to Salva Kiir, Mayardit’s forces in South Sudan shortly before a contract with Frontier Services Group was cancelled

- Frontier Services Group owns two of the modified Thrush 510Gs, but since executives learned the craft had been weaponized by Prince, the company has declined to sell or use the aircraft to avoid violating U.S. export controls

- In December 2016, FSG announced its plans to set up a “forward operating base” in Yunnan to provide logistics and unarmed security training services to facilitate One Belt, One Road-related projects in Southeast Asia (Reuters, 2020) (Bloomberg, 2020)

Frontier Services Group Acquires Stakes in Security & Defense College in Beijing

- As part of its strategy to set new industry standards, the Frontier Services Group acquired a 25 percent ownership stake in the International Security and Defense College in Beijing, which trains Chinese security contractors and managers for international deployment (Nantulya, 2020)

Chinese Private Security Contractors-How the Model Looks for Now

- As of 2020, China was responsible for more construction projects in Africa than France, Italy, and the United States combined. However, China’s expanded global engagements are fraught with risks. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences notes in its 2020 assessment that 84 percent of China’s BRI investments are in medium- to high-risk countries

- To protect its investments, Beijing has invested in and trained security contractors

- The true number of Chinese private security contractors, however, could be much higher, Chinese State Owned Enterprise spend about $10 billion annually on security, according to the Beijing-based China Overseas Security and Defense Research Center

- Security contractors take on added significance in light of all these considerations, as they can handle tasks that would be too controversial for government forces while relieving growing pressure within China for the PLA to be used more proactively abroad (Jamestown, 2020)

De Faakto Forecast-Chinese PMC/PSC Model Will Emulate Chinas Maritime Militia in Grey Zone & Hybrid Warfare

- The Chinese Maritime Militia is an effective auxiliary mechanism of the Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN). This seagoing naval militia engages in the ordinary support roles of the regular navy, but more importantly, it operates in a different space as a grey zone operator. On occasion the militia operates autonomously; alternatively it functions within the command structure of the PLAN. As a grey zone operator the maritime militia will engage in activities that the regular Chinese navy can not. This allows the Chinese regular navy to avoid increased tensions on the world stage, with adversaries in contentious maritime environments. The maritime militia is able to conduct activities that could escalate to war, should PLAN naval ships be employed. Activities the maritime militia engages in may be considered irregular or asymmetrical in nature. (De Faakto, 2020) Actions include; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, sabotage, contested water skirmishes, obstruction, reef/island development, mine laying, concealment missions, spying and ambush. The maritime militia is exceptional in two areas of operations; missions that require small vessels which can linger unnoticed for long periods of time, and obstruction missions where contested waters are saturated with militia vessels as part of “cabbage strategy.” (Erickson & Kennedy, 2016)

- One of the most interesting examples of Grey Zone operations conducted by the Chinese maritime militia is that in countering the US spy ship, USS Impeccable. The Impeccable while monitoring the submarine base at Sanya was sent warnings by the Chinese naval & coast guard vessels to leave the area. When the Impeccable did not, the ship was swarmed by Maritime Militia trawlers, which not only blocked its passage, but used grapple hooks to snag the Impeccable’s towed sonar array used to track submarines. The Impeccable might have seen the Chinese warships or Coast Guard cutters as threatening enough to fire on them. The innocent-looking militia trawlers were able to get the job done without a shot being fired. (Asia Times, 2019) The maritime militia of China is a formidable force, which offers an understated, pragmatic and grassroots approach to modern naval warfare. The irregular and asymmetrical nature of the sea militia coupled with the no-nonsense logistical capability makes it a force multiplier not seen in many modern navies, and one could argue the activities carried out by maritime militias are a form of low profile naval special operations.

Photo Courtesy of Ministry of National Defense The Peoples Republic of China & China News (2020)

What is Chinas Maritime Militia?

- Chinas Maritime Militia is a citizen sailor organization of seafaring personnel, many are fisherman skilled in maritime operations, and commercial seamanship which is easily transferred to navel security operations and navy support; it is a reserve or auxiliary mechanism of the Peoples Liberation Army Navy (PLAN)

- The Pentagon describes the Chinese maritime militia as “a subset of China’s national militia, an armed reserve force of civilians available for mobilization” (Defense News, 2019)

- There is a primary component of the maritime militia, which trains regularly and is more skilled than the less active ordinary component with basic skills and less frequent training (Erickson & Kennedy, 2016)

- Andrew S. Erickson Professor of Strategy at the U.S. Naval War College China Maritime Studies Institute describes “The Maritime Militia as an irreplaceable mass armed organization not released from production and a component of China’s ocean defense armed forces [that enjoys] low sensitivity and great leeway in maritime rights protection actions.”

What Are Some of the Roles of Chinas Maritime Militia?

- Pentagon’s 2019 China Military Power Report says, the maritime militia force “plays a major role in coercive activities to achieve China’s political goals without fighting”

- China’s armed forces is employed in so-called gray zone operations, or “low-intensity maritime rights protection struggles,” at a level designed to frustrate effective response by the other parties involved (Defense News, 2019)

- The maritime militia will confront other states’ fishing and naval vessels, and prevent incursions along the coast

- Militia members often serve as the first responders in emergencies since they are already distributed out across the seas (Erickson & Kennedy, 2016)

- The best-trained and best-equipped members engage in overt paramilitary activities such as the harassment of foreign vessels operating near Chinese-held islets or dangerous standoffs with vessels from neighbouring states (Defense News, 2019)

Employing Retired Chinese Soldiers Abroad in the Private Sector

- Contractors create employment for veterans, an issue of paramount importance to China, given the government’s complicated relationship with demobilized servicemen and women in the country who now number 57 million

- In recent years, veterans have mounted over fifty major protests demanding better benefits. Such demonstrations have undermined the CCP’s standing and threatened the PLA’s latest phase of demobilization and modernization

- Security firms help relieve some of that pressure

Chinese Security Contractors, Profiles of Some of the Players

Photo Courtesy of Zhongjun Junhong Security Service Co (2021)

Zhongjun Junhong Security Service has a Sea Guard branch that protects Chinese ships transiting the Gulf of Guinea to the Sulu Sea in the Philippines. Its overseas security personnel are exclusively former officers of China’s special forces, marines, and amphibious forces, according to its English company profile. Zhongjun also supports Chinese fleets and State Owned Entities by providing offshore armed guards for logistics protection, port security, training of maritime guards, and consulting on antipiracy measures. According to its website, it coordinates security operations through over thirty overseas branches and bases in coastal locations like Durban, South Africa; Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; Mombasa, Kenya, Moroni in the Comoros; and Toamasina, Madagascar (Nantulya, 2020)

The Hua Xin Zhong An Group Also Known As HXZA Company is focused on maritime security, especially along the East African coast. HXZA’s core services include armed maritime security, K&R response, executive protection, static site security, security training, risk assessment, and security technology integration. HXZA’s expansion abroad was ignited by the requirement to follow their Chinese clients’ internationalization process, especially the State Owned Entities in the oil and gas extraction sectors (Arduino, 2020)

Photo Courtesy of China Africa Project (2019)

The Hua Xin Zhong An Group was founded by PLA veterans in 2004. Since 2011, it has deployed armed guards aboard Chinese shipping fleets sailing through African waters in support of the PLA Navy’s antipiracy operations. It is one of the few security firms permitted by the Chinese government to carry weapons abroad. Notably, it also has a near-monopoly on providing onboard armed security for China Shipping Container Lines (CHCL) and the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO), two of the world’s largest shipping operators, which are also escorted by PLA Navy vessels in the Gulf of Guinea and the Gulf of Aden. COSCO provides the logistical backbone for China’s naval operations in these maritime domains, underscoring the linkages between China’s State Owned Entities (SOEs), security contractors, and armed forces. On dry land, Hua Xin Zhong An Group, operates like most of its peers by providing protection for important individuals, security consulting, and risk assessments for its clients. It also supplies advanced security technologies for surveillance and early warning capabilities. Its website states that its core business model is to “reduce our dependence on labour” and “use . . . technology and tools to make our service more effective” (Nantulya, 2020)

The Haiwei Group was founded in 2015 through the incorporation of several Chinese PSCs in response to the demand for the protection of Chinese investors overseas, mainly in BRI countries. Haiwei includes 18 overseas branches in Cambodia, Laos, Malaysia, Kyrgyzstan, Tanzania, Hong Kong, etc.; as well as 11 maritime escort bases. Haiwei’s first African branch was located in Tanzania, following the same pattern as all Chinese PSCs moving abroad in that the branch followed an important client investing in the region. The Haiwei group, which is one of the few Chinese companies that has achieved state certification (Arduino, 2020)

Photo Courtesy of China Security Technology Group (2021)

China Security and Technology Group provides maritime escorts known as Sea Dragons. It notes in its Mandarin listing that it recruits from China’s naval special forces brigade and that its Sea Dragons also participate in the PLA Navy’s escort missions in the Gulf of Aden and the Gulf of Guinea. The firm was registered in 1994 by demobilized PLA officers and initially focused on serving domestic clients involved in construction projects. It employs over 30,000 personnel and was projected to be operating in around thirty countries worldwide by 2020, according to its English listing. (The 30,000 figure includes staff in China.) Its CEO, Tang Feng, describes it as a “Going Out” force that supports “the great strategic initiative ‘Belt and Road,’” a claim that firmly positions it to help advance Chinese national security and foreign policy objectives. The China Security and Technology Group’s African operations are coordinated from Algeria, Angola, Mozambique, and Kenya, according to its website. Its main clients are Chinese shipping fleets and SOEs, as well as Chinese diplomatic facilities including embassies in Sri Lanka and Mozambique. (Nantulya, 2020)

Resources

The Footprint of Chinese Private Security Companies in Africa-Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies-Alessandro Arduino (2020) https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5652847de4b033f56d2bdc29/t/5e7a733475a31172316a05d5/1585083189926/WP+35+-+Arduino+-+Chinese+Private+Security+Companies.pdf

Chinese Private Security Contractors: New Trends and Future Prospects-Jamestown Foundation- Sergey Sukhankin (2020) https://jamestown.org/program/chinese-private-security-contractors-new-trends-and-future-prospects/

SWJ Factsheet: Observing Wagner Group – An Open Source Intelligence Study-Small Wars Journal-S.A. Cavanagh (2018) https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/swj-factsheet-observing-wagner-group-open-source-intelligence-study

Open Source Backgrounder: Djibouti, Foreign Military Bases on the Horn of Africa – Who is There? What are They Up To? Small Wars Journal De Faakto Intelligence Research Observatory (2019) https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/open-source-backgrounder-djibouti-foreign-military-bases-horn-africa-who-there-what-are

SWJ Factsheet: Chinas Territorial Stratagem – Extending Military Range & Influence through Reclamation & Occupation of the Spratly Waters, South China Sea-Small Wars Journal-S.A. Cavanagh (2018) https://smallwarsjournal.com/jrnl/art/swj-factsheet-chinas-territorial-stratagem-extending-military-range-influence-through

CHINAS MARITIME MILITIA-INTELLIGENCE NOTES-De Faakto Intelligence Research Observatory (2020) https://defaakto.com/2020/02/12/chinas-maritime-militia-intelligence-notes/

Chinese Security Contractors in Africa-Carnegie-Tsinghua-PAUL NANTULYA (2020) https://carnegietsinghua.org/2020/10/08/chinese-security-contractors-in-africa-pub-82916

Chinese Private Security Contractors Along the BRI-Belt & Road News-Dr. Sergey Sukhankin (2020) https://www.beltandroad.news/2020/05/18/chinese-private-security-contractors-along-the-bri/

Frontier Services Group Ltd-Reuters (2020) https://www.reuters.com/companies/0500.HK

Frontier Services Group Ltd-Bloomberg (2020) https://www.bloomberg.com/profile/company/DVNHF:US

China’s Private Army: Protecting the New Silk Road, How will Beijing provide security for Chinese personnel and infrastructure along the Belt and Road? The Diplomat- Alessandro Arduino (2018) https://thediplomat.com/2018/03/chinas-private-army-protecting-the-new-silk-road/

China’s Private Military And Security Companies: ‘Chinese Muscle’ And Reasons For US Engagement – Analysis-Eurasia Review- Christopher Spearin (2020) https://www.eurasiareview.com/07072020-chinas-private-military-and-security-companies-chinese-muscle-and-reasons-for-us-engagement-analysis/

China’s use of private companies and other actors to secure the Belt and Road across South Asia-International Institute for Strategic Studies-Meia Nouwens (2019) https://www.iiss.org/blogs/analysis/2019/04/china-bri

WHO GUARDS THE ‘MARITIME SILK ROAD’? War on the Rocks- VEERLE NOUWENS (2019) https://warontherocks.com/2020/06/who-guards-the-maritime-silk-road/

THE CHINESE MILITARY SPEAKS TO ITSELF, REVEALING DOUBTS-War on the Rocks-DENNIS J. BLASKO (2019) https://warontherocks.com/2019/02/the-chinese-military-speaks-to-itself-revealing-doubts/

Chinese private security companies go global-Financial Times Staff (2020) https://www.ft.com/content/2a1ce1c8-fa7c-11e6-9516-2d969e0d3b65

China’s South China Sea Militarization Has Peaked-Foreign Policy-Steven Stashwick (2019) https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/08/19/chinas-south-china-sea-militarization-has-peaked/

China’s Pursuit of Overseas Security-Rand Corporation-Timothy R. Heath (2018) https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/research_reports/RR2200/RR2271/RAND_RR2271.pdf

OSINT Research Contribution Assistance provided by,

Recherchebureau Hermes

info@recherchebureauhermes.nl

Images

Photo Courtesy of People’s Daily Online (2013) http://en.people.cn/90786/8285633.html

Photo Courtesy of China Africa Project (2019) https://chinaafricaproject.com/analysis/qa-growing-demand-in-africa-for-chinas-private-security-contractors/

Photo Courtesy of Africa Intelligence (2020) https://www.africaintelligence.com/mining-sector/2020/06/16/erik-prince-wins-key-security-contract-from-chinese-mining-giant-cnmc,109237564-eve

Photo Courtesy of China Security Technology Group (2021) http://www.cstghk.com/en/group/p/6.html

Photo Courtesy of Zhongjun Junhong Security Service Co (2021) https://www.zjjhgroup.com/en/

Photo Courtesy of LinkedIn (2018) https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/erik-prince-his-chinese-owned-frontier-services-group-pj-wilcox/

Photo Courtesy of Jetphotos (2015) https://www.jetphotos.com/photo/8108449

Photo Courtesy of Belt and Road News (2020) https://www.beltandroad.news/2020/09/09/belt-road-initiative-has-been-an-important-brand-name/

Photo Courtesy of Air Tractor 802 (2021) https://802u.com/aircraft-capabilities/

Photo Courtesy of African Quarters (2019) https://africanquarters.com/libyan-officials-say-has-evidence-of-russian-mercenaries-in-war/

Photo Courtesy of Arab Unreported (2019) https://medium.com/@arabunreported/erik-prince-covertly-operating-dmcc-in-iraq-document-reveals-405582a523a

Editing Assistance Provided By,

MC & CS